Shorebirds, Shrimp Farms, and Conservation Opportunities

Introduction

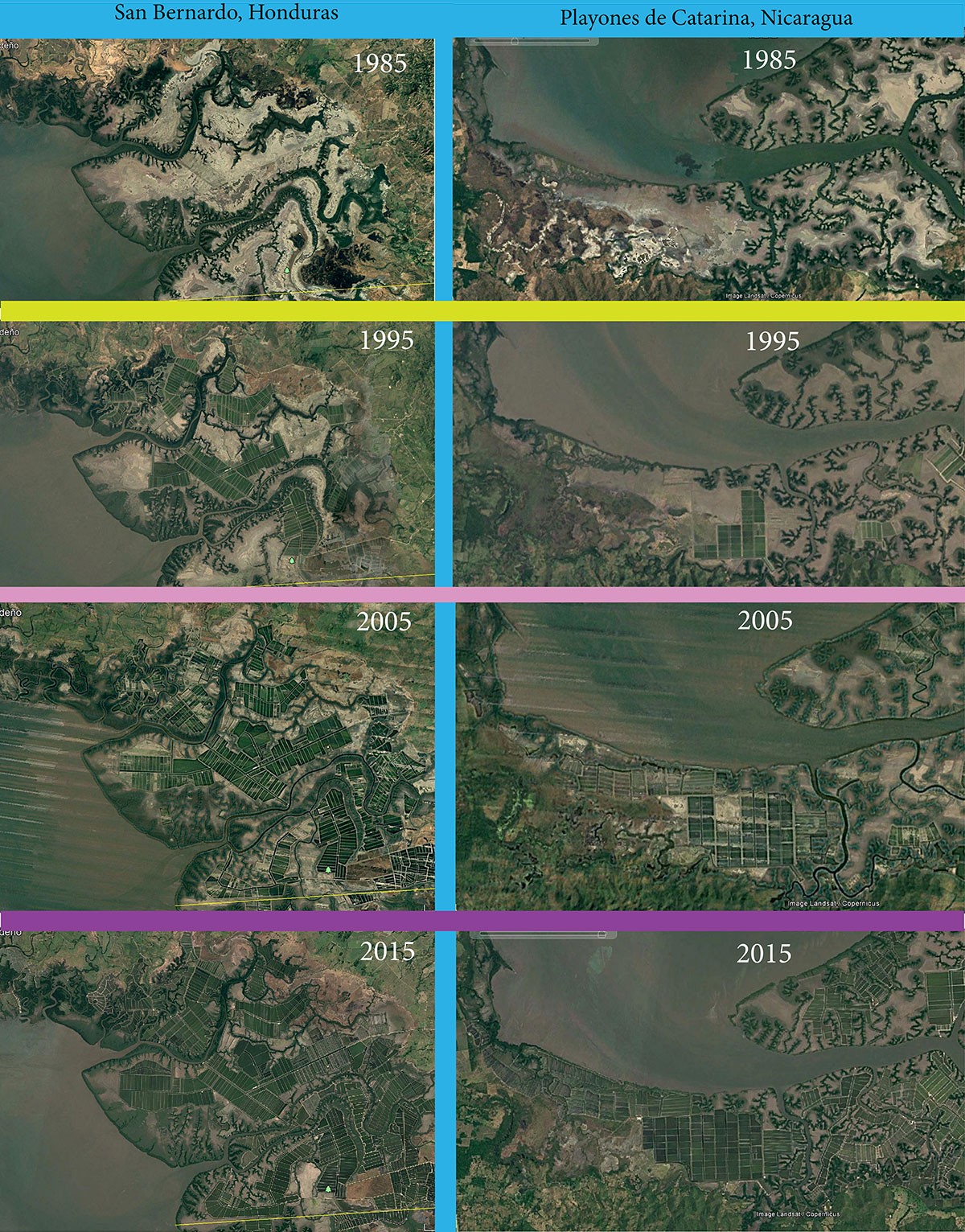

Much shorebird habitat has been altered for commercial shrimp farms on the coasts of Mexico, Central, and South America, but shorebirds often use these farms and their natural and modified habitats for opportunistic foraging and roosting. Between 20 – 27 shorebird species and tens of thousands individuals have been observed using a single shrimp farm (e.g., at the Gulf of Fonseca, Morales et al. 2019, and in Mexico, Navedo and Fernández 2018). Willets, American Oystercatchers, Western Sandpipers and Black-necked Stilts are among the species which make use of the shrimp farms for roosting and foraging in the drained shrimp ponds between production cycles. There lies an opportunity for the shrimp farm industry and shorebird conservation practitioners to work together towards improved conditions for shorebirds.

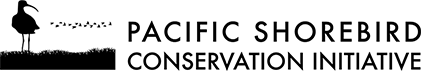

Figure 1. Shrimp farms and salt ponds located along the Pacific Coast of Central America, 2019. Map: Rachel Layko/National Audubon Society.

Background

Shrimp farming is an aquaculture production method that yields high-quality shrimp for human consumption. Shrimp farming in Latin America began in the 1970s and gained momentum in the 1990s with improvement in production practices and capital investments from international development funds. Shrimp farms operate in different ways, but semi-intensive farms are a complex of human-made ponds and dikes, developed primarily within tidal mangrove estuaries with freshwater sources to aid production.

As of 2016, there were approximately 60,000 hectares (ha) in production in Central America (Guatemala to Panama), another 60,000 ha in Mexico, 19,000 ha in Brazil and 220,000 ha in Ecuador (Figure 1. ARAP 2008, SENASA 2016, INPESCA 2016, El Salvador Ministry of the Environment 2016, FAO 2018, Global Aquaculture Alliance 2018). Within Latin America, the nations with the largest volume of production are Ecuador, Mexico, Brazil, Honduras, and Nicaragua. Mexico and Brazil primarily produce shrimp for domestic markets, but other countries, like Nicaragua, export their products.

Threats and opportunities related to shrimp farm development

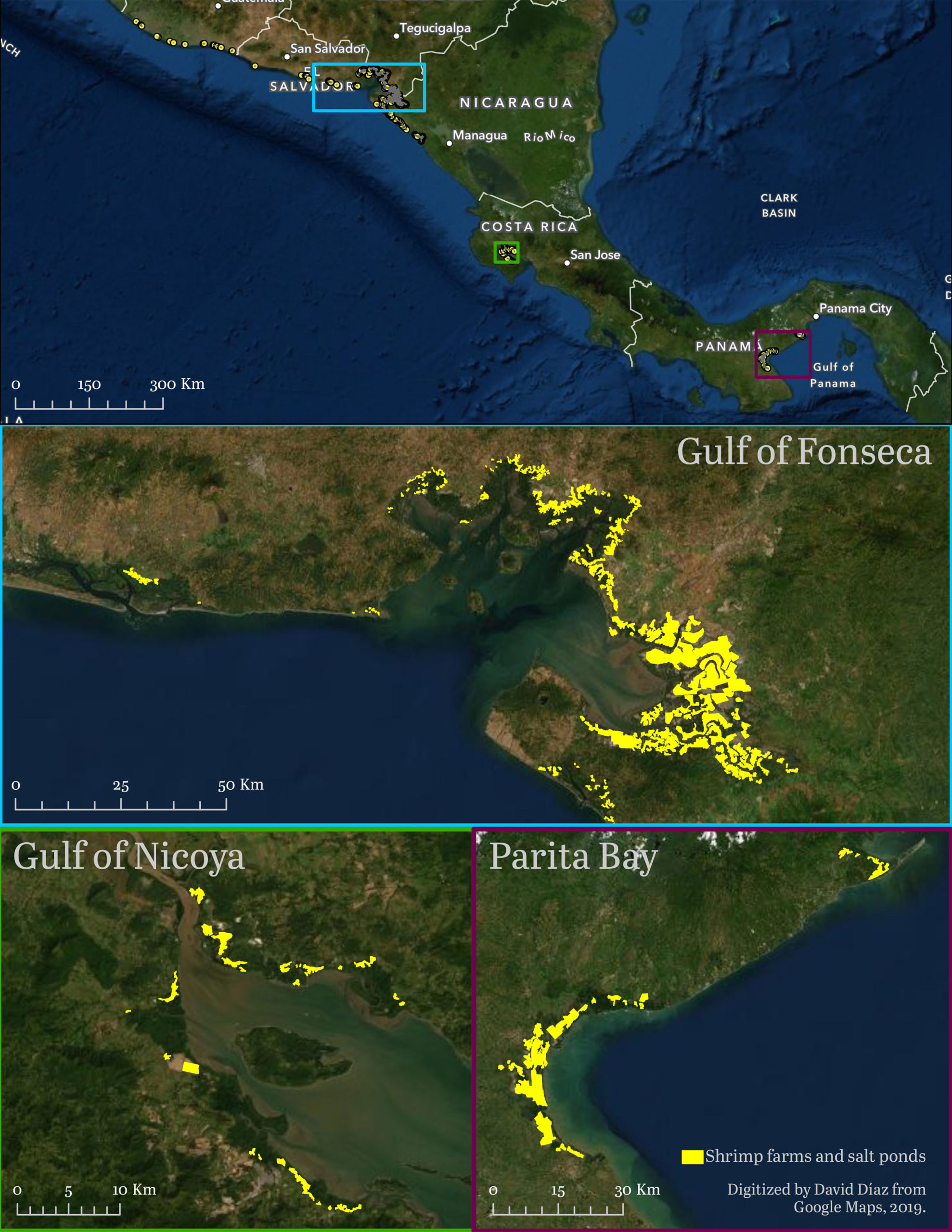

During the 1990s, international lending institutions and national governments promoted the expansion of shrimp aquaculture in Latin America as an important industry for rural economic development (Queiroz 2014). As a result, shrimp aquaculture development has contributed to the loss of 38% of mangrove habitats in the Americas (Valiela et al. 2001). However, within mangrove ecosystems the specific habitat frequently converted to shrimp farms are salt flats (Berlanga-Robles et al. 2011). The adjacent maps illustrate how shrimp farming has expanded in Honduras and Nicaragua between 1985 and 2015, converting natural salt flats habitats into shrimp ponds (Figure from Morales et al. 2019).

Shrimp aquaculture can directly impact shorebird habitats by destroying or reducing habitat quality in salt flats and marshes, seasonal freshwater wetlands, and mangrove estuaries. Shorebirds also make use of the shrimp farms’ dikes for roosting, and the daily farming operations can disturb birds. Once farms are developed, they also tend to encourage other infrastructure and activities including: 1) building of dams, roads, and utility lines; 2) extraction of mangroves for wood; 3) alteration of nursery fish habitat; 4) modification of wetlands 5) compounded conflicts of water management; and 6) increased industrial pollution (Benessaiah and Sengupta 2014).

Figure 2. Shrimp farming has expanded in Honduras and Nicaragua between 1985 and 2015, converting natural salt flats habitats into shrimp ponds (Figure from Morales et al. 2019).

Studies suggest that once semi-intensive shrimp farms ponds are established, they may benefit migratory shorebirds during the non- breeding season. For example, one of the benefits of shrimp farms ponds is that they provide feeding habitat after the shrimp harvest. The farms also offer supra-tidal roosting areas on the dikes, particularly those that do not have vegetation. Negative impacts can be minimized and positive benefits can be enhanced through the development of sustainable best management practices that reduce damage to natural and human-modified habitats that surround the shrimp farms (Navedo and Fernández 2018).

How shorebirds make use of natural and shrimp farm habitats

Shorebirds make use of a variety of coastal habitats for foraging, roosting and breeding. Daily tidal cycles regulate the availability of shorebird food: Mudflats and shorelines are exposed during low tides and invertebrates are within the reach of probing shorebird beaks, whereas the flooding of high tides makes food unavailable. Shorebirds make use of these daily cycles to forage rapidly during low tides and rest when tides are high and food is unavailable.

Shorebirds feed in ponds at shrimp farms when water levels are low after a harvest of shrimp, usually for a 3- to 4-day period. More frequently, shorebirds can be found roosting on the farm’s dikes or other non-production areas during high tides (Morales et al. 2019).

Focal species and their ecological needs

Twenty-three species of shorebirds have been observed using shrimp farms in Central America (Morales et al. 2019) and 25 species in northwest Mexico (Navedo and Fernández 2018, Navedo et al. 2017). Many of these species are migrants, breeding primarily in North America. Some species also nest in and around shrimp farms including American Oystercatcher, Black-necked Stilt, Wilson’s and Snowy Plovers (J. Van Dort, J. Fonseca, G. Fernández and S. Morales, personal communications).

The following 11 species are the most abundant shorebirds using shrimp farm habitats in Latin America throughout the Pacific Americas Flyway:

- Black-necked Stilt

- American Avocet (Mexico only)

- American Oystercatcher

- Wilson’s Plover

- Semipalmated Plover

- Whimbrel

- Marbled Godwit (Mexico only)

- Western Sandpiper

- Semipalmated Sandpiper

- Short-billed Dowitchers

- Willet

The composition and abundance of shorebird species found in shrimp farms depend on the presence of shorebirds in the natural habitats surrounding the shrimp farms, such as intertidal mudflats, natural salt flats, and mangroves, as well as the ecology of the shorebirds and their habitat use. Places that have more complex natural wetlands habitats have higher species richness in both natural habitats and at shrimp farms. Relative abundance of shorebirds varies widely from 5,000 to 25,000 shorebirds at shrimp farms in Mexico during the nonbreeding period (Navedo et al. 2015, Navedo and Fernández 2018). Results from a simultaneous survey of the Gulf of Fonseca estimated approximately 136,000 shorebirds using shrimp farm habitats (Van Dort 2017, Note: This estimate is likely low due to the relative effort they were able to give to this habitat type during the surveys. Surveys were completed during a 2-day period in January).

American Oystercatchers and other shorebirds use shrimp aquaculture pond dikes as roost sites at Delta del Estero Real, Nicaragua. Photo: Orlando Jarquín/Quetzalli Nicaragua

Shrimp farm ponds recently drained after a production cycle; a good foraging area for shorebirds. Photo: Salvadora Morales/Manomet.

Conservation need and goals

Coastal mangrove habitats and adjacent salt flats are productive ecosystems that benefit human wellbeing through the delivery of ecosystems services, such as subsistence agriculture, artisanal fisheries, and provision of building materials and fuels (Lacerda 2002). Mangrove estuaries are vital nursery habitats for subsistence and commercial fisheries (Hutchinson et al. 2015). Given the importance of mangrove ecosystems, including salt habitats, people working to protect shorebirds and their habitats while maintaining economic opportunities have identified the following goals:

- Limit the impact of shrimp aquaculture by discouraging development in sensitive areas of high importance to birds and fish.

- Mitigate the impact of shrimp farms on shorebird populations by implementing best management practices and market-driven valuation.

Working Group members (left to right) Victoria Galán (SalvaNatura, El Salvador), Salvadora Morales (Manomet, Nicaragua), Julia Salazar (Salinera Santa Alejandra, Honduras) and Mayron Mejía (Asociación Hondureña de Ornitologia, Honduras) co-hosting a booth at the industry’s 12th Central American Aquaculture Symposium.

Members of the Working Group met in Panama City in January 2019 to discuss strategies, actions, and solutions for improving shrimp farms practices to benefit shorebirds.

Conservation Strategies

In 2018, a Shorebirds and Shrimp Farm Working Group was created to more effectively build expertise and resources to support, guide, and encourage efforts by shrimp farmers to adapt production practices to increase their value for shorebirds and other wildlife. The Working Group is comprised of shorebird and wetlands biologists, research scientists, and shrimp farm industry representatives. If you are interested in joining the Working Group, please contact Salvadora Morales, WHSRN Conservation Specialist, smorales@manomet.org.

Strategy 1: Manage and protect natural habitats in and nearby shrimp farms.

Quetzalli Nicaragua and the Executive Office of the Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network have established a working relationship with shrimp farmers to develop best management practices to benefit shorebirds.

Read more about this project:

» Shorebirds and the Shrimp Industry

Strategy 2: Create opportunities to educate producers, local communities, and authorities on techniques to improve production that increase the value of their product and benefit shorebirds and other wildlife.

Working Group members from Nicaragua, El Salvador, Honduras, and Colombia have been attending aquaculture tradeshows to network with producers and their cooperative organizations.

Read more about this project:

» Shorebirds at the Central American Aquaculture Symposium

Strategy 3: Develop new shorebird-specific best management practices.

Developing best management practices with shrimp producers will increase the value of these human-modified habitats for foraging and roosting shorebirds. To inform and guide the Working Group’s efforts, an assessment of the shrimp farming industry and shorebirds was completed in 2019.

Read more about this project:

» Shorebirds and Shrimp Farming

Strategy 4: Investigate the ecology of shorebirds in shrimp farms and surrounding habitats.

Researchers have been working on various aspects of the ecology of shorebirds using shrimp farm habitats including projects in Northwestern Mexico, the Gulf of Fonseca (Nicaragua, Honduras and El Salvador), and Brazil. More recently, Cornell University’s Coastal Solutions program has a fellow working on shrimp farming and salt production in Guatemala.

Read more about these projects:

» Bird Ecology Lab

Literature cited

Autoridad de los Recursos Acuaticos – Panama (ARAP) 2008. Listado de productores de camarón marino en estanques en Panamá. Autoridad de los Recursos Acuaticos, Panama.

Benessaiah, K. and R. Sengupta 2014. How is shrimp aquaculture transforming coastal livelihoods and lagoons in Estero Real, Nicaragua? The need to integrate social-ecological research and ecosystem-based approaches. Environmental Management 54:162–179.

Berlanga-Robles, C. A., A. Ruiz-Luna, G. Bocco, and Z. Vekerdy 2011. Spatial analysis of the impact of shrimp culture on the coastal wetlands on the Northern coast of Sinaloa, Mexico. Ocean and Coastal Management 54: 535–543. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2011.04.004.

El Salvador Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales 2016. Report on the shrimp aquaculture concessions in El Salvador. https://www.transparencia.gob.sv/institutions/marn/documents/concesiones-y-autorizaciones.

Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) 2018. The state of world fisheries and aquaculture 2018 – Meeting the sustainable development goals. Rome. 227 pp.

Global Aquaculture Alliance 2018. https://www.aquaculturealliance.org/advocate/shrimp-farming-industry-in-ecuador-part-1/

Hutchison, J., P. Z. Ermgassen, and M. Spalding 2015. American Fisheries Society Symposium 83:3–15.

Instituto Nacional de Pesca (INPESCA) 2016. Base de datos de camaroneras concesionadas en Nicaragua. Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Nicaragua.

Lacerda, L. D., Ed. 2002. Mangrove Ecosystems: Function and Management. Berlin; New York; London, Springer-Verlag.

Martínez-Córdova, L., M. Porchas and E. Cortes-Jacinto 2009. Camaronicultura Mexicana y Mundial: ¿Actividad sustentable o industria contaminante? Revista Internacional Contaminación Ambiental. 25: 181–196

Morales, S., O. Jarquín, E. Reyes, and J. G. Navedo. 2019. Shorebirds and Shrimp Farming: Assessment of Shrimp Farming activities on Shorebirds in Central America. Western Hemisphere Shorebird Reserve Network, Manomet, Massachusetts, USA.

Navedo, G. J. and G. Fernández 2018. Use of semi-intensive shrimp farms as alternative foraging areas by migratory shorebird populations in tropical areas. Bird Conservation International. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270918000151

Navedo, G. J., G. Fernández, J. Fonseca, N. Valdivia, M. C. Drever and J. A. Masero 2017. Identifying management action to increase foraging opportunities for shorebirds at semi-intensive shrimp farms. Journal of Applied Ecology 54: 567–576.

Navedo, G. J., G. Fernández, J. Fonseca, and M. C. Drever 2015. A potential role of shrimp farms for the conservation of nearctic shorebird populations. Estuaries and Coasts 38: 836–845. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12237-014-9851-0

Servicio Nacional De Sanidad Agropecuaria – Honduras (SENASA) 2016. Base de datos de fincas camaroneras de Honduras. Servicio Nacional De Sanidad Agropecuaria – Honduras.

Queiroz, L. D. S. 2014. Industrial shrimp aquaculture and mangrove ecosystems: A multidimensional analysis of a socio ‐ environmental conflict in Brazil. P.h. D dissertation, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals, Spain. https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/tesis/2014/hdl_10803_286034/ldsq1de1.pdf

Van Dort, J. 2017. Conteo trinacional de aves playeras en el Golfo de Fonseca. Reporte sin publicar. Manomet, Inc., USA.

Valiela, I., J. L. Bowne, and J.K. York 2001. Mangroves forests: One of the world’s most threatened major tropical environment. BioScience 51:807–815.